One of the most radical pharaohs

in Egypt’s ancient history was the controversial Pharaoh Akhenaten, father to future Pharaoh Tutankhamun (formerly Tutankhaten).

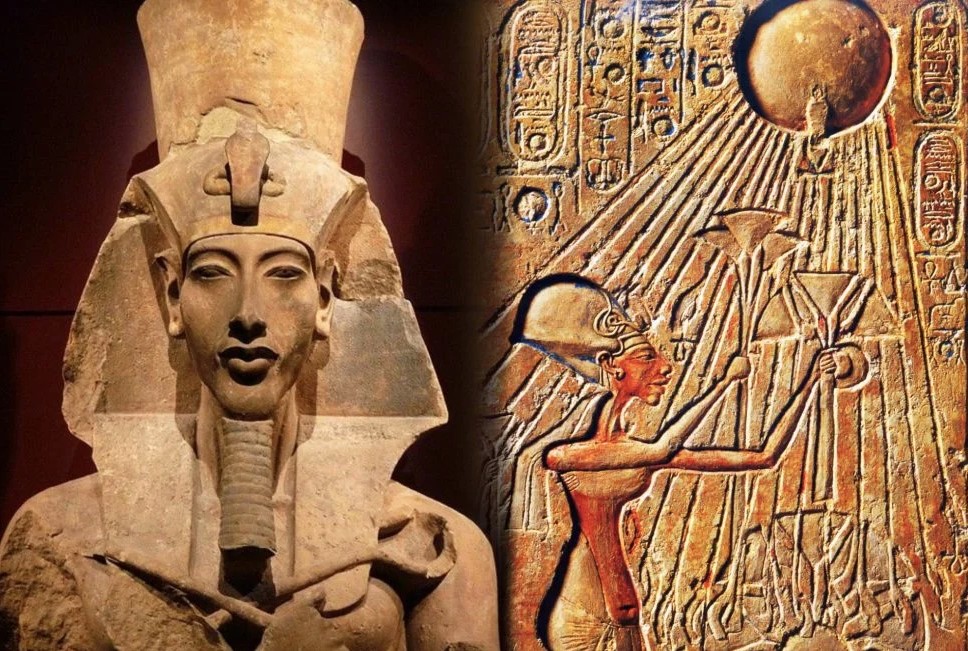

Akhenaten, formerly known as Amenhotep IV (ancient Egyptian: jmn-ḥtp, meaning “Amun is satisfied) was considered a bit of an unusual-looking (most likely due to genetic abnormalities) “heretic” king because he is noted for abandoning the traditional ancient Egyptian religion of polytheism and introducing Atenism, or worship centered around Aten, the sun-disk god as the sole deity, thereby introducing one of the earliest forms of monotheism.

He declared himself the sole intermediary between the god Aten and the people, making the royal family the essential link to the divine.

Akhenaten, who changed his name from Amenhotep IV to reflect his devotion to the god Aten, founded a new capital city named Akhetaten meaning “horizon of the Aten.” The modern town of Amarna was built near the ruins of this ancient city, and historians named the Amarna Period of Egyptian history after it.

While Aten was a solar deity,

the new religion centered on him was a significant departure from the traditional worship of Ra, the falcon-headed god, and elevated Aten to a supreme, sole deity. This also led to the diminishing of other gods, particularly Amun, and the powerful Amun priesthood.

(Note: Amun was originally the god of Thebes, associated with air and fertility, while Ra was the sun god. Over time, particularly during Egypt’s New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE), the two deities were merged into the single, supreme god Amun-Ra, representing the combined power of the visible sun and the invisible air. This fusion was a political and religious move to create a singular, supreme deity embodying both Amun’s local authority and Ra’s universal power.)

In addition to sweeping changes in religion, his reign also introduced changes to architecture and art, specifically a new artistic style known as the Amarna style, which was more naturalistic and emphasized intimate depictions of family life, unlike the more formal, traditional Egyptian art.

He was a skilled administrator and diplomat, and his new building techniques, such as the use of small, easily manageable “talatat” blocks, sped up construction. His reign also spurred a number of other industrial and technological advancements in building, glass making, statuary, and textile production, as evidenced by the archaeological remains at Akhetaten.

Upon his death after a tumultuous reign,

the young King Tutankhamun (originally known as Tutankhaten, meaning “Living Image of the Aten”)’s dedicated his own reign to restoring the traditional Egyptian religion, reverting his father Akhenaten’s changes. This restoration included moving the capital back to Thebes and transferring royal remains from the abandoned city of Akhetaten (Amarna) for safekeeping.

This restoration included moving the capital back to Thebes (now Luxor) and it is widely accepted that he had his family’s royal remains transferred from the Royal Tomb in the abandoned city of Akhetaten (Amarna) to the Valley of the Kings, for safekeeping.

King Tut later changed his name from “Tutankhaten” to “Tutankhamun” to honor the god Amun.

Reburial and lingering questions

Akhenaten was likely reburied in tomb KV55 as the mummy in KV55 has been widely accepted as his based on DNA evidence showing it belonged to the father of Tutankhamun, but the coffin was desecrated, the face mask was ripped off, and the hieroglyphs on the coffin were chiseled out.

The skeletal remains are accepted to be those of the father of King Tut, but the estimated age at death for the mummy conflicts with historical sources about Akhenaten’s age at death, leading some to believe the mummy is Akhenaten’s successor, Smenkhkare.

Learn more here.

Akhenaten Heretic King

Photo credit: Austin Crouch, Culture Frontier

Leave a comment